| Dr. Chetan Hazaree R&D Project Manager, LafargeHolcim Innovation Center France |

Building road infrastructure is an intensive process involving land-use, human resource, materials, and energy. The predominant goal of conventional road building with a typical design life of 15-30 years is minimizing the upfront construction costs. This is unlike some critical national infrastructure like nuclear or hydropower plants, which are designed atleast for 100 years. As such, roads undergo a faster life-cycle resulting into less sensitive long-term co-existence with environment and society. However,roads built with long-term, harmonious environmental-social-economic considerations are much more sustainable.

To support her economic and social development, India has set herself on an ambitious journey of building her National infrastructure. Road building is at the forefront of this diversified plan. From expressways to rural roads, the speed of road construction is also accelerating the speed of consuming limited resources.Withfinite land, natural resource, and energy availability, it is increasingly becoming critical to effectively manage these resources for the envisioned growth. In addition, existing ways and methods need a critical review for their future applicability. This brings a chance to learn from other Nations that have walked a similar path. Hidden within these lessons are opportunities,when explored could lead to wholesome, stable, and resilient developments.The more learned Nations are implementing the solutions with a single motif of making earth more sustainable than before. One such recent concept, albeit in its infancy and yet to be characterized adequately is that of circular economy (CE). This article explores the necessity and urgency of implementing CE for the Indian road sector.

Grey Versus Green (Circular) Economy

Grey infrastructure is built without concern for sustainability, guided instead by upfront costs and conventional, prescriptive design standards and construction specifications. These include projects that have little concern for alternate modes of transportation, ecologically sensitive areas, wildlife, the wider community, and other issues of sustainability. On the other hand, Green infrastructure considers social and environmental issues, alongside economic concerns. These projects attempt to address environmental issues such as habitat fragmentation, deforestation and the destruction of wetlands, and social concerns such as alternative transport and public health. (1)

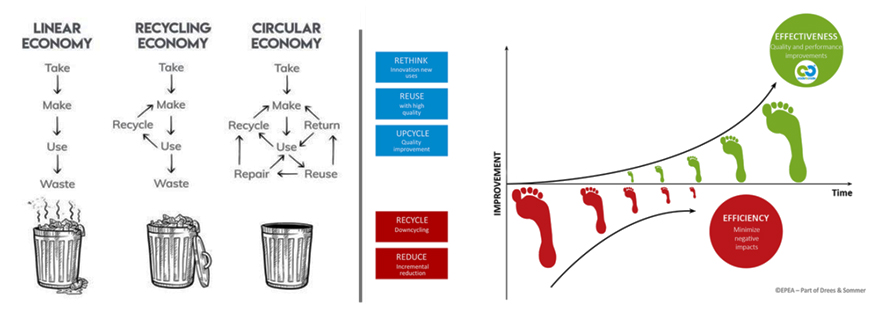

Grey infrastructure utilizes principles of linear economy and is often characterized by one-way, linear, eco-efficient use of materials using “take-make-dispose” approach. This product-focused economy is shorttermed and often leads to substantial waste generation, pollution, and down-cycling. In this economic systemvalue is created by producing and selling as many products as possible. Green infrastructure on the contrary, is based on CE characterized by eco-effective, “reduce-reuserecycle” plans. Focusing on perpetual, long-term, multi-cycle use, this economy often leads to creative upcycling that focuses on services. Refer Figure 1. The World is gradually getting convinced that CE is a viable, sustainable, and unavoidable alternative. Besides, it is compatible with the inherent interests of the corporations, as it is aligned with the competitive and the strategic frameworks and it is capable to enrich the contract between the consumers and the producers (2).

Fig. 1: (Left): Linear-Recycling-Circular Economies (2) (Right): Eco-Effectiveness and Eco-Efficiency (3)

Circular Economy, Defined

ACE aims to redefine growth, focusing on positive society-wide benefits. It entails gradually decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources, and designing waste out of the system, while being ecologically intelligent (5). Underpinned by a transition to renewable energy sources, the circular model builds economic, natural, and social capital. It is based on three principles viz.

– Design out waste and pollution;

– Keep products and materials in use;

– Regenerate natural systems (6)

In an analysis of 114 definitions of CE, one of the comprehensive definitions that emerge is the following. An economic system that replaces the ‘end-of-life’ concept with reducing, alternatively reusing, recycling, and recovering materials in production/distribution and consumption processes. It operates at the micro level (products, companies, consumers), meso level (eco-industrial parks) and macro level (city, region, nation and beyond), with the aim to accomplish sustainable development, thus simultaneously creating environmental quality, economic prosperity and social equity, to the benefit of current and future generations. Novel business models and responsible consumers enable it. (7)

Fig. 2: Circularity Strategies within the Production Chain, in the Order of Priority (8)

Strategies

A higher level of circularity of materials in a product chain means that those materials remain in the chain for a longer period, and can be applied again after a product is discarded, preferably retaining their original quality. Several circularity strategies exist to reduce the consumption of natural resources and materials, and minimise the production of waste. They can be ordered for priority according to their levels of circularity as summarized in Figure 2 (8). As per these hierarchies, it may be noted that recycling is not far from linear economy.

It may be noted that while various strategies exist for the transitioning from linear to circular economies, the key however is in having an integrated approach. The solution will be realized when Economic and Social models are closely synced with Ecological model and intelligence. A study in the Netherlands has enumerated the benefits of transitioning to CE as shown in Figure 3. It has also been cautioned that realising these opportunities is no easy feat. Investments and new alliances between companies will be required, and the traditional, already established companies will likely slow the transition down. Government policy will often be needed to overcome barriers and to change the perception of the importance of natural resources. (9)

Fig. 3: Benefits of CE for the Netherlands

Initiatives, Challenges And Enablers For CE

It is vital to note that the business community popularized CE, which currently to a large degree is legislation driven. There are many listed at the European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform (10), while other examples of such legislation include,

i). Closed Substance Cycle and Waste Management Act in Germany (1996);

ii). The Recycling-Based-Society in Japan (2002);

iii). Circular Economy Promotion Law in China (2009);

iv). EU Resource Efficiency Scoreboard (2015);

v). The Raw Materials Scoreboard (2016) (9)

The findings of an industry-wide survey conducted in Europe summarized following as the key challenges to the implementation of CE:

i). Lack of awareness at Industry-wide level;

ii). The absence of a broad consensus of what the CE looks like in the built environment;

iii). The parts of the supply chain, such as clients and designers, have little knowledge on how to adopt CE principles is likely to impede uptake of circularity in the short term;

iv). Lack of incentive to design for end-of-life issues;

v). Lack of market mechanisms to aid greater recovery and an unclear financial case;

vi). Fragmented nature of the construction industry;

vii). Existing stock of buildings and infrastructure where circularity principles have not been adopted.

All stakeholders ranked a clear business case as the most important enabler, with commercial viability identified in the breakout sessions as fundamental to shift current practices. Technical challenges including the lack of recovery routes and the complex design of buildings, whilst significant, are likely to be overcome to some extent through further research on enabling technologies and sharing of knowledge. (10)

CE And India

The challenges listed above are applicable to Indian economy as well. For India to achieve continued economic growth, poverty alleviation, hunger elimination, human development, andenvironmental improvement, new transformative and radical solutions are needed rather than incremental improvements. While India has committed to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), termed the Agenda 2030, progress is hampered by haphazard urban development and ineffective regulatory controls. Moreover, the focus on long-term sustainability is often trumped by social and political turbulence, as well as unexpected disruptions such as terrorism, industrial accidents and extreme weather events. Despite all these, a recent FICCI-Accenture study suggested that India through various strategies could unlock approximately half-a-trillion dollars of economic value by 2030 through adoption of CE business models (12). A report based on high-level economic analysis of three focus areas key to the Indian economy and society viz. cities and construction, food and agriculture, and mobility and vehicle manufacturing, shows that a CE trajectory could bring India annual benefits of INR 40 lakh crore (USD 624 billion) in 2050, and would in addition reduce negative externalities (13).

Some of the measures that could help transitioning to CE include:

i). Product eco-labelling schemes;

ii). Tax incentives;

iii). Design standards that include resource efficiency and use of secondary raw materials;

iv). Standard business models and financial mechanisms for end-of-life product recovery;

v). Social innovations;

vi). Special Economic Zones for establishment of recycling capabilities; Preferential “green” procurement schemes;

vii). Raising consumer awareness and stakeholder consultations on policy implementation experiences and possible improvements.

Stimulation of voluntary compliance and innovation will be critical to the future success of waste management and CE programs. Moreover, enlightened policies provide a foundation for change, but successful policy implementation will require stimulus for innovative demonstration programs at the local and regional level. (12)

Fig. 4: Value Realization Potential from Circular Business Models by 2030 (13)

The Case Of Ambuja Cement

Responsively responding and embarking her journey, Ambuja Cement has started working towards The Sustainable Development Ambition 2030, which provides a broad framework for the company’s strategies to meet the challenges in four broad thematic areas: Climate, CE, Water & Nature, and People & Communities. Refer Figure 5.

Indian Road Sector And Circularity

Indian economy boasts of 62,15,797 km (16) of roads constructed on the foundations of robust demand, attractive opportunities, higher investments and conducive policies. While this appears attractive, it must also be appreciated that most of these constructions are based on linear economy or at the most and partly recycling economy. This brings a cautious two-fold opportunity for the upcoming road construction projects. The first is in regard to dealing with the existing road network and second one to transition to an integrated, rapid and effective CE.

This is a unique opportunity for India to define its CE driven road infrastructure. The new concept of sustainable road (18) is characterized by the following:

i). constructed to reduce environmental impacts;

ii). designed to optimise the alignment (vertical and horizontal including considerations of ecological constraints and operational use by vehicles);

iii). resilient to future environmental and economic pressures (e.g. climate change and resource scarcity);

iv). adaptable to changing uses including increased travel volumes, greater demand for public and active (cycling and walking) transport; and

v). able to harvest the energy to power itself

Fig. 5: A Case for CE in Construction Materials (15)

Awareness – An Essential First Step

One of the first steps for transitioning to CE is to educate and create awareness about its urgency and need. Efforts from governments, industry, the research community, and society will be needed to overcome these challenges and accelerate the efficient use of materials. Policy and action priorities could include the following:

i). Train, build capacity and share best practices;

ii). Develop regulatory frameworks and incentives to support material efficiency

iii). Adopt business models and practices that advance CE objectives

iv). Shift behaviour towards material efficiency

v). Increase data collection, life-cycle assessment and benchmarking

vi). Improve consideration of the life-cycle impact at the design stage and in climate regulations

vii). Increase end-of-life repurposing, reuse and recycling (19)

Favourable Policy Framework

Road construction is largely done using public finance. Encouraging sustainable road construction with public funds can be done by regulating and implementing favourable policies, a sampling of which is summarized in Table 1.

Innovation Is The Key

Any road’s lifecycle starts from its concept and takes the path of materials, design, construction, use, maintenance and preservation and end of the life-cycle (19). In each of these aspects, innovation is the key. Figure 6 summarizes a broad list of such initiatives that need “all-stakeholder integration”

Fig. 7: Key Initiatives Required for Sustainable Pavements and CE

Summary

Transitioning to CE for sustainable road infrastructure is viable, sustainable, and unavoidable. India has a two-fold challenge-cum-opportunity viz. dealing with a 6.22 Million km of existing roads mostly built with the principles of linear economy and effectively yet swiftly transitioning to a CE. Such transitioning needs to be founded on very strong principles of integration from all stakeholders supported adequately with commensurate patience and resource engagements. Creating awareness, educating, deploying effective vision, having an efficient and workable policy framework, regulated implementation, and radical innovation could be some of the initial steps.

Note: The views expressed in this paper are those of the author.

References

1. Bassi, A M, McDougal, K and Uzoki, D. Sustainable asset valuation tool: Roads. Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada : International institute for sustainable development, 2017.

2. Linear Economy Versus Circular Economy: A Comparative and Analyzer Study for Optimization of Economy for Sustainability. Sariatli, F. 1, 2017, Visegrad Journal on Bioeconomy and Sustainable Development, Vol. 6, pp. 31-34.

3. [Online] https://thercollective.com/blogs/r-stories/circular-economy-vs-linear-economy.

4. EPEA. Cradle to cradle: Beyond sustainability. [Online] https:// epea.com/en/about-us/cradle-to-cradle.

5. Crade to cradle: remaking the way we make things. Braungart, Micheal and McDonough, William. s.l. : vintage Classics, 2008.

6. Foundation, Ellen Macarhur. What is a circular economy? A framework for an economy that is restorative and regenerative by design. [Online] https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ circular-economy/concept.

7. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Kirchherr, J, Reike, D and Hekkert, M. 2017, Resources, conservations & recycling, Vol. 127, pp. 221-232.

8. Potting, J, et al., et al. Circular economy: measuring innovation in the product chain. s.l. : Universiteit Utrecht, 2017.

9. Bastein, T, et al., et al. Kansen voor de circulaire economie in Nederland, TNO-rapport. s.l. : Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu, 2013.

10. European Union. European circular economy stakeholder platform. [Online] https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/en.

11. Measuring the circular economy – A multiple correspondence analysis of 63 metrics. Parchomenko, A, et al., et al. 2019, Journal of cleaner production, Vol. 210, pp. 200-216.

12. Circular economy in construction: current awareness, challenes and enablers. Adams, K T, et al., et al. s.l. : Institution of civil engineers, 2017, Waste and resource management, pp. 1-11.

13. Steps toward a resilient circular economy in India. Fiksel, J, Sanjay, P and Raman, k. 2021, Clean technologies and environmental policy, Vol. 23, pp. 203-218.

14. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circular Economy in India: Rethinking growth for long-term prosperity. 2016.

15. Accenture & FICCI. Accelerating India’s circular economy shift, A half-trillion USD opportunity. New Delhi, India : s.n., 2018.

16. Ambuja Cement. Sustainable Development Ambition 2030. [Online] https:// www.ambujacement.com/Sustainability/Sustainable-Development-Ambition-2030.

17. Mnistry of Road transport and highways, GoI. Annual Report 2020-21. MoRTH. [Online] https://morth.nic.in/annual-report. 18. Newman, P, hargroves, C and Desha, C. Reducing the environemtnal impact of road construction. Australia : Sustainable Built Environment National Research Centre (SBEnrc), 2021.

19. International Energy Agency. Material efficiency in clean energy transition. International energy agency. [Online] 2019. https://www.iea.org/reports/ material-efficiency-in-clean-energy-transitions.

20. FHWA. What can we do to improve pavement sustainability? Federal Highway Adminstration. [Online] https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/pavement/ sustainability/what.cfm.